<<

A game of truth and deception -

New photo and video works by Manuel Frolik at Städtische Galerie Dresden.

Who would not like to pose with the great Joseph Beuys on a photo? Unfortunately, he already died in 1986. But that doesn´t prevent Manuel Frolik from presenting himself on a Polaroid with Beuys. It is not the only picture in Froliks exhibition “Infinite Quest“ at Städtische Galerie Dresden, that shows him with some great artist. Also singer and poet Nick Cave gives his youthful face to the artists camera.

May all art should be fraud at the end? Or may it even be megalomania? After all, Cave and Beuys belong to the most influential artists of their metier. Obviously this is a game about truth and possibilities. It deals with artistic strategies of self-staging and the construction of tradition-lines of masters and students: standing in the shadow and rising above ones idols, even this is in these pictures. As well as the 15 minutes of fame for everyone.

On a deeper meaning these faked photographs say something about our picture-hungry world, in which the picture always tells the truth (or at least claims it). Even Stalin already knew that no picture is forgery-proof, that it can be processed and manipulated; as he whipped Trotzki out of history afterwards. With nowadays possibilities of picture editing even moving pictures can be faked astonishingly easily. Welcome to the brave new world of fake-pictures! In addition to this, the faked presence of Beuys is virtually harmless.

For Manuel Frolik, born 1979, the examination of fake and original is a recurring element of his work: whether if it is the faithful adaption of an image or even with the help of faked images, the key question is the one for authenticity. Because art is always a challenge with quotations and adoptions of the old masters, it is necessary to question the authenticity delusion – repetition and variation – actually the history of art has to be considered in this terms.

Frolik, who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden, also refers back to elements of the naive children’s play in his work. At the same time he demystifies our ideas of childhood in his video „Tribe of Yola“, which is the centre of the exhibition. The scenery of the film seems to be dystopian. Some kids go for an adventurous and dangerous trip through some kind of a “no man’s land“. If they are really just playing…? Childhood is also present in Froliks sculptures: almost spooky are the kids-sculptures made from silicon rubber. Everything, until the hair on their heads, is imitated faithfully.

In a mixture of hyper realistic reproductions on the one hand and the use of found materials on the other, the question for the appropriation of reality by the artist always arises. As a viewer one smiles in the face of the game of truth and deception. In the best sense of the word, Manuel Frolik is an entertainer.

Marlen Hobrack, in DRESDNER Kulturmagazin 02 / 2019

<<

from the programme of the 32. Kassel Dokfest, November 2015

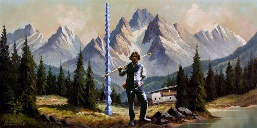

Dresden 2014 / video projector, HD player, amplifier, 2 speakers, subwoofer, object (37 min.)

This hiking tour seems to have no end and yet the hiker presents himself with a steady flow of power

in his forward thrust, which leads him through this forest, through green meadows, along river courses

or through swamps with dead branches and over rough rocks. He remains to pursue his path with

determination. Neither effort nor hardship can be sensed, nor an optimistic mood or fatigue. This is

why we – while following him cinematically – cannot predict how long he has been en route, let alone

how long he will be able or willing to continue this way. After some time, one notices that the

landscapes begin to repeat themselves and one begins to suspect that the hiker is moving in circles.

And indeed, this work is an experiment with the video loop as a cinematic structure. What seems like a

repetition is a sequence of singular films, which have been shot at the same location but are cut

together from different sources of film material. The consequence of scenes and therefore the

landscapes of the seven five-minute films are the same, the shots and details vary. The question

arises, how long we would we watch a film before noticing that the replay actually is not a replay and

what it means when – after seven films – the actual repetition starts; when the film is really looped in

its presentation as an installation.

The hiker himself and his presence seem to fall a bit out of time. A vest and a striped shirt, a backpack

and a wandering stick are far from today’s functional wear and so he seems much more like a

contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich than of our days. Therein lies a desired image, which has

existed for a long time in our culture. The longing for a simple life in harmony with nature already

existed in antiquity in the imagination of a rural Arcadia. Other examples are the idea of the great hike

in Johann Gottfried Seume’s book “Spaziergang nach Syrakus” (“Walk to Syracuse”, 1803) or the

imagination of a retreat to the woodlands in Henry David Thoreau`s cult book “Walden” (1854). All of

these images are also images of masculinity; blue prints, which today are interchangeable and

available as one identity among many. In his work Manuel Frolik stages such spaces and images,

myths of male freedom and self-determination; for example as a sailor, as a mechanic or as the cool

friend of Dash Snow or Kurt Cobain. But this does not happen without ironic distance: his sailor is a

corpse, and Dash Snow as well as Kurt Cobain are also already dead, therefore “cool” per se.

The hiker undertakes his hike as a projection in a forest worker’s hut. The image appears as a kind of

slide picturing longings, like a photo-wallpaper presses the dream of a far away world onto the

domestic walls. Frolik adds objects to this room, which make it seem like a life-size doll house or like

rooms of the past frozen into big dioramas, which one can come across in local history museums.

Holger Birkholz

<<

SPFX, or: Nature after Nature.

Opinion statement regarding Manuel Frolik’s silicone studies by Prof. Dr. Dietmar Rübel, Chair of Art History Academy of Fine Arts Munich, 2018.

Two years ago, Manuel Frolik completed a series of seven silicone sculptures shaped like chunks of wood and roots. The intricate studies are presented on dark wooden bases with curved legs, whereby at first glance the artefacts seem like bonsai trees or particularly opulent cacti.

Yet viewers are quickly filled with astonishment and react with a shudder. For on closer inspection it becomes clear that human and animal hair protrudes from these plant- and wood-shaped forms, and the objects’ peculiar shades of colour have the appearance of unhealthy skin tones, or evoke an incarnation of something deathly ill or no longer human. What grips viewers emanates from the special effects, or SPFX for short, which permeate the sculptures, making the impossible – such as person-wood-animal-hybrids – possible, while simultaneously revealing and reflecting upon the underlying methods of the artistic practice. The sculptures seem like found objects from a former film set: ‘As-If objects’ that come from horror or science fiction films and radiate the distinct characteristics of creepiness. And the artist does indeed use the materials and techniques of make-up artists, or works closely with them. Using expensive materials and laborious craftsmanship, the seemingly natural horrors emerge in irritating realism – even though these absurdities are completely artificially produced.

In this work, Manuel Frolik examines spellbinding questions around aesthetics and the materiality of the (post-)modern, and particularly around the present debates about ‘nature after nature’ and ‘Dark Ecology’. Indeed, the effect of his two materials – hair and rubber – is closely linked to debates that began around the year 1800 about the materiality of the arts. The real hair he implants into the silicon forms brings to mind one of the foundational texts of modern sculpture: Johann Gottfried Herder’s 1778 book Plastik: Einige Wahrnehmungen über Form und Gestalt aus Pygmalions bildendem Traume (Sculpture: Some observations on shape and form from Pygmalion’s creative dream), and the passage which describes the aesthetic horror – or from today’s point of view ‘the subversive potential’ – which the poet experienced from seeing hair on sculptures. There it states: “The little individual hairs send shudders through us. Like a chip out of a knife blade, they are just something that impairs the form, and that does not belong there”. This also indicates the extent to which modern art is tied to its materials, and how experimentation with new materials and substances has emancipated itself from form – to which Herder believed materiality did not ‘belong’.

A special place in the history and theory of the arts, in addition to cast iron and steel, is held by rubber. In everyday speech, rubber refers to a heterogeneous group of natural and man-made materials resembling India rubber, and which can be moulded, pressed, cut, bonded, sewn or foam-formed. Thereby it remains very flexible and thus, when touched or lightly shaken, Manuel Frolik’s sculptures begin to vibrate and wobble in an eerie fashion. Due to the flexibility of natural rubber, there are applications for it in almost every area of our daily lives. Natural rubber manufactured from latex – the milky sap of various tropical plants – was employed in Africa and in Central- and South America as early as two thousand years ago. Unstable raw rubber reached Europe around 1750, but it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that it could be made more durable through vulcanisation, making this elastic, pliable material suitable for industrial production.

After 1909, rubber was also produced synthetically. Silicone rubber has been available for use since 1945. Its molecular chain is no longer made of carbon, but of alternating silicone and oxygen atoms instead. This astounding material is the main component of the silicone series of works, and even today its aesthetic effect is baffling – certainly comparable to early descriptions that came out of the first Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. As Gottfried Semper noted in 1860, in the first volume of his principle theoretical work Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten oder praktische Ästhetik (Style in the technical and tectonic arts; or, Practical aesthetics): “Only recently has an important natural material brought forth a type of revolution in the most diverse fields of industry, and this is due to its remarkable malleability, with which it yields and lends itself to all purposes. I speak of gummi elasticum, or caoutchouc (...) the stylistic range of which is the broadest imaginable, since its almost unlimited sphere of application is that of imitation. This material is, as it were, the mimic among useful materials”.

The giddiness caused by this versatile material and its endless possibilities led to rubber being used in arts and crafts during the ‘long nineteenth century’ to imitate other natural materials.

And this quality also comes to the fore in Manuel Frolik’s series when he produces deceptively real replicas of chunks of wood and roots that he collected earlier on long hikes. These surrogates are thus based on actual natural forms from which the artist makes laborious moulds, then producing casts which he paints with an airbrush. Besides the specific material properties which the artist uses extremely skilfully, the final stage – the coloured version of the work – adds another dimension, and one which has been in particular demand when working with rubber in twentieth century fine art. The fact that synthetic latex milk or silicon rubber constitutes an amorphous material with skin-like qualities makes it particularly suitable for depicting alternate concepts of corporeality due to its mimetic malleability.

In their body-related art, many artists – from Marcel Duchamp and Louise Bourgeois through Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke to Matthew Barney and Nathaniel Mellors – make use of the notion that slumbers in rubber of a corporeality with no clear boundaries. In Manual Frolik’s work this anthropomorphic materiality gives rise to hybrid creatures, in which the human body has almost completely united with animal and vegetable components. Only the individual hairs sprouting on the flesh-coloured found objects of his silicone series evoke human figures in these absurd forms – although in fact only two of the sculptures feature real human hair: the rest is from

animals. We are seeing the last traces or phases of a mutation in a post-human world, and they can also appear as thing-forms or organic vestiges. Manual Frolik leaves the endeavour of humanity behind as a hairy problem.

In all of this, something is created that may constitute a speculative romanticism – but it is logically executed as Nature after Nature. For it is clear that the series of silicone sculptures is also about departing from the romantic concept of nature that has characterised European aesthetics since around the year 1800.

In precisely the spirit of theoreticians such as Timothy Morton or Bruno Latour, everything that surrounds living creatures is understood as nature here – whether that be synthetic materials, everyday objects or complex machines. In visualising a so-called “Dark Ecology”, the world should be viewed from a non-human perspective, thus also from the viewpoint of animals or plants – which could account for the sculptures’ uncanny allure.

However, there is no “back to nature” in these theories – and this is the greatest horror that Manuel Frolik’s sculptures elicit.

For there is no more ‘nature’. Finished. Gone. It is a matter of no longer understanding that which was once nature as the antithesis of culture, and instead seeing the achievements of humanity, but also of animals and plants, as a part of today’s environment – as a complex network of hybrids.

Thus, Manuel Frolik’s series is initially bewildering because of its eerie materiality and its manifestation as human-wood-animal hybrids. With its speculative romanticism based on special effects but also on an initial orientation on inevitability, it possibly offers a rethinking of Nature after Nature

<<

Phytophilia Dresdense, 2017

from: remembering the future, exhibition catalog

Manuel Frolik´s process-based work is known for its artistically appropriation and alienation of ´found footage´ or detailed reproductions of hyper realistic or amorphous sculptural figures and objects. He questions authenticity and authorship and plays with our ideas of fake and original.

For “remembering the future“ Frolik worked together with the collection Herbarium Dresdense and the Botanical Garden of the Technical University of Dresden. About dealing with the typological appearance of herbarium vouchers, some of which go back to the 18th century, Frolik made scans of new plant material from the Botanical Garden, that recur on the historical evidence, and have an independent pictorial transformation of the material.

Gwendolin Kremer, 2017

Jessica Buskirk:

Interview with Manuel Frolik

Jessica Buskirk: How would you describe your work for

Remembering the Future?

Manuel Frolik: It’s a photographic work inspired by

Herbarium Dresdense, focusing on exotic plants from the Botanical Garden

in Dresden. Originally I had a different idea. I was in the hebarium looking for material for sculptural works, but I decided to

work on a photographic project because I was so interested in the way that botanists handle their plant material.

Jessica Buskirk: Can you be more specific? What’s remarkable about their approach?

Manuel Frolik: I don’t think the botanists are even aware of it, since it’s part of their daily work, and they’re used to it. But for

me as an outsider it was interesting to see even just how the plants in the herbarium are displayed and how people interact with

them. Since the plants for the herbarium are dried, their shape is drastically different compared to their original appearance or

living plants. For botanists, certain characteristics of the plants are significant and have to be presented in the herbarium. The

plants are dried, they’re dead, their stems and stalks are severely bent if they’re too long, etc. That was actually the first thing I

noticed in the herbarium. I asked the scientists about the reasons for this and the resulting changes. They said they are so

aggressive in order to make it clear that it is a human intervention. That means a plant is severely bent so that it is obvious that

it didn’t grow that way, but rather was “brutally” forced into this unnatural shape. It

should look as if a human has had a hand in

its shape for the display.

Jessica Buskirk: It surprised you because it is so unaesthetic?

Manuel Frolik: I wouldn’t say unaesthetic. It has a totally different aesthetic quality. That’s what interests me.

Jessica Buskirk: You’ve described how the botanists’ approach inspired your work. Do you see your photography as a

continuation of that or more as a counterpoint to it?

Manuel Frolik: No, I’m really trying to do exactly what I saw the botanists do. The difference between my work and the images

in historic herbariums, some of which are 200 years old, is that I try to leave out the visible historic traces. That means I don’t

use yellowed paper, old handwriting, etc., which play a big part in the experience when we view an old herbarium today. I’m

going to use high-resolution scans under an acrylic sheet so that the presentation has a cooler feeling and a high-tech look. I try

to exclude the historic aspects and concentrate on how the plants are presented in this format. That’s why it’s so important to

me to start with the actual processes used in herbariums.

Jessica Buskirk: Which has impressed you the most?

Manuel Frolik: I was looking for peculiarities. I looked at a total of 1000 sheets or more in the herbarium. I found two of them

simply breathtaking. These two displays really opened up a new viewing experience for me. The others were more within the

realm of the familiar, the expected. And so I try to hone in on these special cases in my work.

Jessica Buskirk: Can you speak a little more about the scanning process, its concrete steps and how your pictures will look in the

end?

Manuel Frolik: It was lucky that there was a good scanner on site at the herbarium. I had already had the idea of scanning the

displays beforehand. With scanning you can get a certain depth of focus. That’s why a scan always looks cleaner overall than a

photograph, which is sharper in the middle than at the edges. There are now scanning processes that make a larger depth of

focus possible, allowing for a depth of focus of about 2 centimeters, so that the parts of the plant that don’t lie flat are still

reproduced well.

Jessica Buskirk: Is the process more important than the product for you, or is that totally not the case? You’re working now in

the herbarium, but as an artist...?

Manuel Frolik: For me the main thing is how the ideas materialize. That means the photographs that end up hanging on the wall

are the focus. Of course, how they were created plays a significant role, but the resulting work is what’s important.

education

| 2011-2013 |

master student with Prof. Eberhard Bosslet HfBK Dresden |

| 2011 |

diploma |

| 2007 – 2011 |

sculpture and extensive installation with Prof. Eberhard Bosslet HfBK Dresden |

| 2005 – 2007 |

basic studies at HfBK Dresden with Prof. Klaus Michael Stephan and Prof. Carl Emanuel Wolff |

awards and grants

| 2021 |

3rd Prize at PORTRAITS Hellerau Photography Award 2021

|

| 2020 |

travel grant by the state capital of Dresden at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki/Greece

nominated for 8. Merck Prize, 11. Darmstadt Photography Days

|

| 2019 |

project grant by the Cultural Foundation of the Free State of Saxony

|

| 2017 |

project funding by Liebelt Stiftung Hamburg

|

| 2016 |

work scholarship by Stiftung Kunstfonds Bonn |

| 2015 |

nomination: Golden Cube at 32. Dokfilmfest Kassel

purchases of the Cultural Foundation of the Free State of Saxony |

| 2014 |

nomination: Märkisches Stipendium für Bildende Kunst 2015 |

| 2013 |

project grant by the Cultural Foundation of the Free State of Saxony

project funding by Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft |

| 2012 |

awardee of Hegenbarth-Stipendium der Dresdner Stiftung Kunst & Kultur der

Ostsächsischen Sparkasse Dresden im Programm des Deutschlandstipendiums |

projects

| since 2016 |

The Kabakon Art House – project space for contemporary art in Leipzig/Germany

www.kabakon-art.de

|

| 2013-2014 |

Salon Pendant - project space for contemporary art Dresden/Germany |

| since 2012 |

Alte Molkerei Radebeul, in Radebeul/Germany |

selected exhibitions/solo

| 2021 |

Tribe of Yola, Lieberose Castle/Brandenburg/Germany

as part of XXVI. Rohkunstbau 2021

|

| 2020 |

Moritaten und Legenden (Morities and Legends), Marcolini Palais Dresden

|

| 2019 |

Infinite Quest, Städtische Galerie Dresden

|

| 2018 |

Jewels, Drawing Room Hamburg

Der ewige Gärtner, Vorhaus c/o Wolf-Lauströer Dresden

Manuel Frolik im Schlafzimmer Sandrock, Schlafzimmer Sandrock Hamburg

|

| 2015 |

the blue jeans and other brand-new stuff, C. Rockefeller Center Dresden

|

| 2014 |

Infinite Quest – Frolik Open Studio 2014, Alte Molkerei Radebeul |

| 2012 |

Eddies Motodrom, STORE Contemporary Dresden

Horses, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden

|

screenings/lectures/selection

| 2021 |

“You don’t play with your food” A workshop in english language about food & art by Manuel Frolik, EU4ART - Alliance for Common Fine Arts Curriculum

Embracing Nature, online screening, Staatl. Kunstsammlungen Dresden, with Studio Olafur Eliason, Manuel Frolik and Khvay Samnang

Susanne Altmann in conversation with Maya Drachsel and Manuel Frolik artist talk in connection to EU4ART workshop’s, winter semester 2021

ROTORADIO – An evening with the radio pieces by Ferdinand Kriwet, Dresden University of Fine Arts

Rediscovered: REITER/IN – The legendary Dresden art magazine from the early 90s, Dresden University of Fine Arts

|

| 2019 |

artist talk for DCA-Weekend! - Johannes Schmidt in conversation with Manuel Frolik, Städtische Galerie Dresden

|

| 2018 |

Tribe of Yola – Preview, Thalia Cinema Dresden

Walkscapes – Der Wanderer, Dresden Academy of Fine Arts

|

| 2017 |

Falk Töpfer´s asking: Manuel Frolik, Das Kapital, Berlin

Der Wanderer, Avant-première - Infra Studio France

|

| 2016 |

Der Wanderer, Neuer Kunstverein Wupperthal e.V.

Der Wanderer, Albertinum - Dresden State Art Collections |

| 2014 |

Der Wanderer, Galerie Brühlsche Terrasse, Dresden Academy of Fine

|

selected exhibitions/group

| 2021 |

PORTRAITS Hellerau Photography Award 2021, HELLERAU European Centre for the Arts / Museum of Science and Technology Dresden

|

| 2020 |

8. Merck Prize at the 11. Darmstadt Photography Days, Designhaus Darmstadt

face look, Kunstverein Gera

|

| 2019 |

TRANS IT, The Derailment, Kingsbury, Texas/USA

vorübermorgen, Kindl - Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst, Berlin

WIN / WIN 9, Halle 14 - Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst, Leipzig

|

| 2018 |

Manuel Frolik/Maya Schweitzer, Polyptyque 2018, Centre Photographique Marseille/France

100, Galerie Axel Obiger Berlin

SALON, Galerie Ursula Walter, Dresden

Reisegruppe Sandrock, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden

Existenz, Oktogon der HfBK Dresden

Aufbruch und Neuanfang #1, Altana Galerie der TU Dresden

|

| 2017 |

100

Paper Tigers Collection, Syndicat Potentiel Strasbourg/France

Knotenpunkt 17, Affenfaust Galerie Hamburg

Mimesis, Galerie Axel Obiger Berlin

DISPLA(Y)CED, Stadtgebiet Dresden/Alte Feuerwache Loschwitz Dresden

Ostrale Bienale, Ostragehege Dresden |

| 2016 |

MENSCHTIERWIR, Affenfaust Galerie Hamburg

IDENDIÄT, Wasserwerk III Hanau

Total – Move Baby, Move!, Neuer Kunstverein Wuppertal e.V.

READY OR NOT, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden

Elbe, Albrechtsburg Meißen

Protect and Bronze, Alte Feuerwache Loschwitz, Dresden

knowhere’s curiosities, CoBox Dresden

SWAT, Galerie Stephanie Kelly Dresden

|

| 2015 |

Monitoring, 32. Dokfilmfest Kassel

Viva Polaroid! Haus der Fotografie Wien/Österreich

Im Inneren der Stadt, Zentrum für Künstlerpublikationen Weserburg Bremen

WIN/WIN 5, Halle 14 Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig

tools, Alte Molkerei Radebeul

Abzocken ohne Anzuecken, Oktogon der HfBK Dresden |

| 2014 |

Märkisches Stipendium für Bildende Kunst 2015, Städtische Galerie Iserlohn

Building Building – Utrecht Dresden Exchange, Das Areal Dresden

Laktosetoleranz, Alte Molkerei Radebeul

when printers print, Salon Pendant Dresden

geradezu momentan, Oktogon der HfBK, Dresden |

| 2013 |

schools of art, The Holden Gallery Manchester/UK

C.A.R. – Talente, Welterbe Zollverein Essen

NEUN, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

Pluralprojekt, Atelierhof Kreuzberg Berlin

Endrahm, Alte Molkerei Radebeul

Manuel Frolik und André Schulze - Hegenbarth-Stipendiaten 2012, Städtische Galerie Dresden

Haut – Oberfläche unter Spannung, Oktogon der HfBK Dresden |

| 2012 |

Laufend anders – fünf Videos, Albertinum/Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

--:--, F14 – Raum für zeitgenössische Kunst Dresden

Quark, Alte Molkerei Radebeul |

| 2011 |

schools of art, Alte Tabakfabrik Linz/Österreich

Jóvenes Artistas II, Centro de Grabado Contemporaneo, Santa Cruz de Tenerife/Spain

Jóvenes Artistas I, El Taller de Arte, Tías/Isla de Lanzarote/Spain

Coop6, Alte Diamantenbörse Frankfurt/Main

International Neighborhood, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden

Diplomausstellung 2011, Oktogon der HfBK Dresden |

| 2010 |

Das Dynamo Bosslet Jugend Fanfest, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden

Klassentreffen, Second Home Berlin Wedding

Arbeit ist das Feuer der Gestaltung, C. Rockefeller Center F.T.C.A. Dresden |

| 2009 |

Portfolio 04/09, Friedrichstadt Zentral Dresden |

| 2008 |

S’geht geiler, Die Art Keuch Ausstellung in Radebeul, Galerie A.A.L. Radebeul |

| 2007 |

Signale Ostrale, Ostragehege Dresden |

publications/selection

| 2021 |

PORTRAITS Hellerau Photography Award 2021

ed. HELLERAU European Centre for the Arts / Museum of Science and Technology Dresden, ISBN 978-3-9821847-0-8 |

| 2021 |

Existenz Kapitel 2: Spuren

artist book, ed. Dorothée Billard and Susanne Greinke, Dresden University of Fine Arts |

| 2020 |

Bizzare Escapes – Humor in Photography

ed. Darmstadt Photography Days, publisher: Kunstforum der TU Darmstadt,

ISBN 978-3-948908-00-3 |

| 2019 |

A game of truth and deception - New photo and video works by Manuel Frolik at Städtische Galerie Dresden, Marlen Hobrack, in DRESDNER Kulturmagazin 02/2019 |

| 2019 |

Manuel Frolik – INFINITE QUEST 2011 – 2018

Catalog, ed. Steven Leonhard, self-published, book on demand,

starting edition 30 pieces |

| 2019 |

unverbesserlich - Index Klasse Bosslet 1997 – 2019

ed. Eberhard Bosslet, ISBN 978-3-00-060615-1 |

| 2018 |

100

exhibition catalogue, ed. Axel Obiger, Oliver Möst, first edition 2018 |

| 2017 |

remembering the future

exhibition catalogue, ed. Gwendolin Kremer (TU Dresden), Andreas Kempe and Patricia Westerholz (Gallery Ursula Walter), ISBN: 978-3-86780-538-4 |

| 2016 |

IDENDIÄT

exhibition catalogue, ed. Marcel Walldorf and Adina Rac-Parlow,

CoCon-Verlag GmbH, ISBN 978-3-86314-339-8 |

| 2015 |

32. Kasseler Dokumentar und Videofilmfest

programme of Dokfest Kassel and the exhibition Monitoring,

ed. Filmladen Kassel e.V., edition 6000, ISBN 978-3-9812605-8-8 |

| 2015 |

Viva Polaroid!

exhibition catalogue, ed. Markus Hippmann, Nikki Harris, Haus der Fotografie Wien, edition 1000 |

| 2014 |

geradezu momentan

exhibition catalogue for the 250th anniversary of Dresden Academy of Fine Arts

ed. Matthias Flügge, Susanne Greinke and Dietmar Rübel, Dresden Academy of Fine Arts,

Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, ISBN 978-3-86984-095-6 |

| 2013 |

Contemporary Art Depot

Catalogue of an exhibition series at Albertinum Dresden, ed. Verena Schneider/Dresden State Art Collection/Sculpture Collection, Sandsteinverlag, ISBN 978-3-95498-056-7 |

| 2013 |

Haut. Oberfläche unter Spannung

exhibition catalogue, ed. Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in cooperation with

Dr. Jule Reuter, extra verlag, edition 500, ISBN 978-3-938370-51-3 |

| 2011 |

HfBK Dresden Diplom 2011

exhibition catalogue, ed. Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, edition 800

|

| 2011 |

Rohmaterial II

Artist book, ed. Peter K. Koch, Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, ed. 150 Stk. |

| 2009 |

Portfolio 04/09

exhibition catalogue /artist book, ed. C. Rockefeller Center for The Contemporary Arts Dresden, edition 40 |